When you read the word “deforestation,” what image comes to mind? If I had to guess, it would be trees being felled somewhere in the tropics — perhaps the Amazon. In the public imagination, tropical rainforests have become almost synonymous with deforestation and environmental destruction generally.

And indeed, there’s no question that at the global scale, tropical forests are being cleared faster than any others today. But deforestation is also happening a lot closer to home (that is, my home — and perhaps yours, too). And not just a little bit. According to estimates by environmental scientist Chris Williams at Clark University and colleagues, the U.S. loses nearly 1 million acres of forest annually — close to the area of Delaware.1 Surprisingly, that puts us roughly on par with the global average deforestation rate.

At an even more local (to me) level, the nonprofit Chesapeake Conservancy recently released a report showing, among other things, that the two suburban Maryland counties bordering Washington, DC — Montgomery and Prince George’s — lost more than 9,000 acres of forest over a recent five-year span. In fact, according to the data, these two counties have a proportional deforestation rate greater than that of the Amazon!2 (I should note that this is my own interpretation of the data, not the conservancy’s.)

This may come as a surprise to you. If we read about these newly treeless locales at all, it’s most likely in real estate listings. We virtually never read about the forests that were cleared. Why is that?

American deforestation 2.0

U.S. forests today are cleared mostly for new housing and development. Just about every major metro area is metastasizing suburban sprawl at its edges, as an increasingly wealthy population pursues an increasingly unsustainable version of the American dream: car-dependent neighborhoods of oversized houses amply separated from neighbors by sprawling lawns. Especially in the heavily forested eastern half of the country, this sprawl often displaces forests.

While some places require developers to “offset” trees they cut down by planting new trees elsewhere, very few prohibit the clearing of trees. In general, if you want to cut a tree on private land in America, you can. (Washington, DC is an exception, where it is virtually impossible to legally remove a tree larger than a certain size.)

I’ve started to think about this phenomenon as “American deforestation 2.0.” It’s different from American deforestation 1.0 — the wave of forest clearing that began after Europeans arrived. Back then, loggers swept from the east coast to the west, picking up the pace as they went and razing one of the world’s great forests in a mere three centuries. At its peak around 1880, the U.S. was putting more carbon dioxide into the air through deforestation than all other countries combined. (Trees are roughly half carbon by dry weight, and when they’re cut or burned, much of that carbon goes into the atmosphere as CO2.)

To this day, the U.S. has emitted more carbon dioxide from forest clearing and land use change than any other country. Because carbon dioxide has a cycling time of centuries, most is still in the atmosphere, warming the planet. Yet we’ve never paid a penny for the impact these emissions are having on people around the globe.

Of course, trees have also regrown and reabsorbed some of that carbon. About one third of the U.S.’s land is forested today (compared to around 46% in the early 1600s), and most of those forests are still growing. But huge areas that were once forested no longer are, and may not be for a long time, because the land is being used for other purposes. As the Indiana-born University of Maryland geographer Matt Hansen often says, there are no deforestation-free soybeans grown in the state of Indiana — because nearly the entire now-agricultural state was once hardwood forest.

And that highlights another point about deforestation: It’s profitable. The first time around, people wanted timber and farmland. Today, people want houses and lawns, and in some cases, more farmland. They also want solar panels, another growing, though still relatively small, driver of modern-day deforestation.

Bottom line: We’re losing trees and all their benefits because people have determined they can make money converting forested land to another use. How large will this new wave of deforestation grow? It all depends on land-use decisions we make in the years ahead. One thing that’s already clear about American deforestation 2.0, however, is that much of the conversion is likely to be long-lasting, because trees won’t easily regrow on land that has been paved, built on or covered in solar panels.

A blind spot for forests?

I’ve thought a lot about why the American media, the environmental community and the public focus so heavily on tropical deforestation and so little on deforestation close to home. As one of countless examples, the Washington Post has a whole series called “The Amazon Undone,” yet hardly covers American deforestation. And the Post is hardly unique.

I think there are several things going on. One is related to narrative. The Amazon, and tropical forests in general, have been exoticized, adding narrative allure. They are often, and inaccurately, described as “pristine” or “untouched,” even though they have been inhabited, used and shaped by humans for millennia.

There’s a particular narrative I call “Amazon exceptionalism,” which portrays the Amazon as the “lungs of the planet” and uniquely important to the global climate. The Post has declared, rather bizarrely, that the Amazon is “the world’s carbon sink.” The troubling implication is that the need to dispose of our carbon pollution gives those of us in the Global North cause to intervene in forests half the globe away.

Our American woods, by contrast, can seem mundane and unexceptional. They’re mostly second-growth (or third- or fourth-growth). And since we see them every day, they become so familiar we often overlook them, even though they provide many of the same benefits that forests in the Amazon do: habitat, carbon storage and sequestration, water filtration, livelihoods, natural beauty.

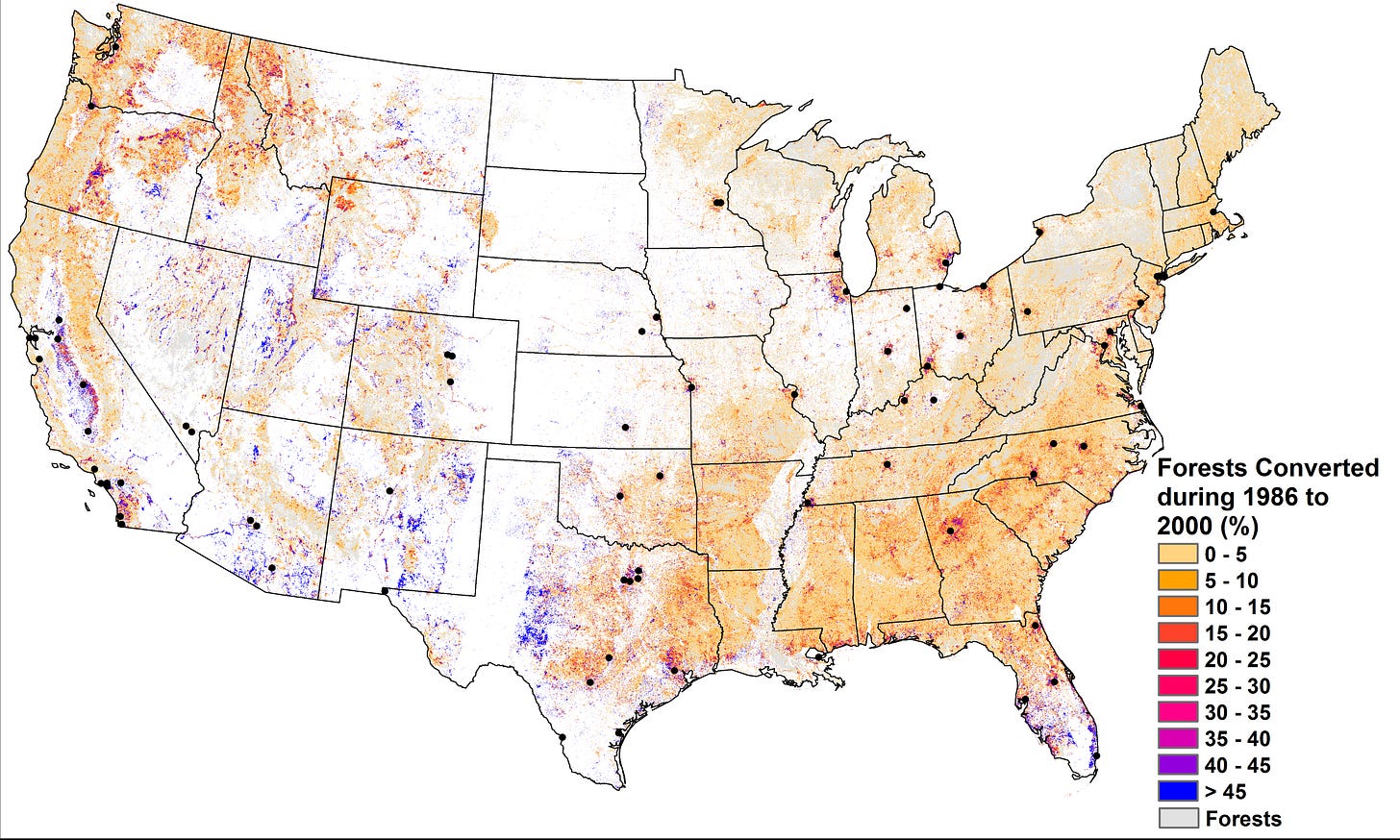

Additionally, forests here are being cleared not along an agricultural frontier, but in little patches around the country, which doesn’t always add up to an alarming tableau. The map below from Williams and colleagues shows where forests were cleared in the late 1980s and 1990s. Note hotspots in growing metro areas like Atlanta, Charlotte, Chicago, Cincinnati, Detroit and DC, all of which continued to expand in the last two decades, likely consuming more forests. In the western U.S., by contrast, conversion to farmland seems to become more common.

I think there may be an even more powerful driver behind the Global North’s obsession with the Amazon and other tropical rainforests: They’re faraway and managed by other people and governments. As such, they can help us offload some of our rich-world climate and environmental guilt. If we can point a finger at cattle ranchers razing the Amazon to produce more beef (and the politicians who enable them), our apparent responsibility for global warming lessens.

Deforestation does emit a significant amount of carbon dioxide. But we need to put this in perspective. As my friend Jag Bhalla recently pointed out, the wealthiest 10 percent of the world — a fortunate group that most likely includes you, me, and everyone else reading this newsletter — emits more CO2 in a few years than all Amazon deforestation to date. So if our goal is to rein in climate change, we should focus most of our attention on the main cause of climate change, which overwhelmingly remains the burning of fossil fuels in wealthy and middle-income countries. Deforestation is a distant second — and globally, it’s already falling.

I don’t want to give the impression that I don’t think tropical deforestation is a problem. I am very concerned, as we all should be, about the threat it poses to the millions of species that live only in tropical forests, which are widely recognized biodiversity hotspots, and to the many people and communities that live in these ecosystems and consider them home.

Conservationists and scientists often tell me that’s what they really care about too, but they feel that only climate-centric arguments can mobilize the resources needed to conserve threatened forests. Perhaps there’s something to that. But I think it’s equally likely that climate-centric framings backfire. After all, if we’re able to get a handle on climate change in the coming decades, would that mean we no longer need to care about rainforests, much less our own forests back home?

Why do forests matter?

This all leads me to a question: How much do the forests we’re losing in the U.S. matter? If the market is saying we want houses and shopping centers more than woods right now, and if our forests in aggregate remain a robust carbon sink, is it actually a problem that some are disappearing?

I asked Williams what he thinks about this. He says the amount of carbon lost from forest clearing in the U.S. is indeed relatively small compared to the enormous quantities that spew from our vehicles, houses, power plants, factories and so on. So even cutting deforestation to zero would have a modest overall climate impact. “The leading values of forests might not really be their carbon stocks,” Williams says. “It’s other things.”

In other words, things like the the stormwater that forests capture, so that it doesn’t cascade all at once into our streams and rivers and estuaries like the Chesapeake Bay, causing flooding and pollution. Things like the homes that forests provide to living creatures, some 80% of which (those on land, at least) live in forests. Things like wood for building the new houses we need. Things like natural beauty and the respite forests can provide for us. I like the way Williams puts it: “The natural capital that’s offered by our forests is something to protect — just like a Renaissance painting.”

I’ve been especially struck by the mounting evidence that being around trees and forests is good for us. Study after study shows that when we’re around trees and forests, we feel better and are physically and emotionally healthier. We might not even notice these trees, yet they still do us good. That makes sense: Our relationship with trees is as ancient as the human species itself.

As forests are pushed farther and farther from the places where we live, fewer and fewer of us are able to benefit from all they have to offer — from the increasingly quantifiable health benefits to the sense of wonder and awe that people often experience in the woods.

There’s also a matter of international politics and public relations. How can we credibly ask other countries to stop deforesting when we’re doing it ourselves — and moreover, when we’ve gotten rich by doing it at massive scale in the past and never acknowledged or paid for it? Brazil’s former president Jair Bolsonaro exploited this kind of hypocrisy when defending policies that increased deforestation. In the end, the Brazilian people elected a leader who promised to protect the Amazon. But it was a close election and could easily have gone the other way.

So what to do? It’s not realistic to never cut a tree again. Especially when we legitimately do need housing and clean energy, to ban any forest clearing would work against other important societal goals; we must be willing to accept some tradeoffs.

But can we improve those tradeoffs to get a better end result? Just in my Maryland town, an older “inner-ring” suburb near the DC border, several vacant lots are crying out for “in-fill” development — sites that could collectively house hundreds of people and dozens of small businesses. Can we push development to places like these where forests are already cleared and thereby take the pressure off outlying forests that we need for their water, (local) climate, health and habitat benefits?

As for clean energy, I wrote last year for the New York Times about how we might lessen conflicts between solar energy and forests.

And we need to broaden the conversation about deforestation so people don’t see it as merely a developing world problem. Let’s acknowledge that it remains a global phenomenon driven by the same market forces that are at work everywhere. And let’s acknowledge that we in the Global North have benefited greatly from past deforestation, and that it’s hypocritical to ask poorer countries to forgo such benefits unless we can offer a different — and credible — development pathway.

I’ll end with a call to my fellow journalists. Part of our job is to put things in context and provide balance. Focusing obsessively on deforestation in poor countries, and ignoring it back home, fails to do that and creates a misleading narrative. Let’s create better journalism about forests.

As always, I’m interested in any thoughts you have on this post, this topic or what you think I should write about next!

Williams’ estimate covers the time period 1986 to 2000. He notes that some time lag is needed to ensure that an area where trees have been cleared has truly been converted to a non-forest use like housing or farmland (in other words, trees are not regrowing). But he has analyzed more recent data and says that so far, it looks like the rate is holding steady or possibly increasing. Other groups such as the World Resources Institute have produced somewhat lower estimates for the U.S. deforestation rate.

I derived this annual rate by dividing the amount of forest lost in Montgomery and Prince George’s County from 2013 to 2018 by the total forested area of the two counties, and then dividing by five. Deforestation rate estimates for the entire Amazon vary widely, but all come in well below the two-county figure. Of course, the scales are vastly different, and the total amount of forest cleared in the Amazon is much larger. It’s also much more likely to be “primary forest” and to contain greater biodiversity.

Thank you for writing about the importance of forests in the US. I enjoyed your article and appreciate your call for more writing about trees. One aspect of reforestation that I am interested in is how agroforestry can restore trees on land currently devoted to annual row crop agriculture. I work for the Savanna Institute, and we are catalyzing the widespread adoption of agroforestry in the Midwest. We recently partnered with Joe Fargione at TNC on a large grant-funded project to scale up tree planting on farms. I think the combination of agroforestry, the Homegrown National Park Movement, and Food Forests can help slow and potentially reverse the deforestation trend. I am working to help people connect with trees in their yards so they can develop a deeper appreciation, commitment, and willingness to advocate for trees.

Worst deforestation is happening in western Ukraine just now

https://gegenzensur.rtde.live/international/162494-kahle-karpaten-wer-ist-fuer/

I could not find it @ english RT, but there are translating programs.

Shifting from wood & coal to oil & gas was very good for forests, but now crazy people spread the idea, that burning fresh biomass is better for what ever, as burning old biomass.