Speaking to the future with loppers and hand saws

Planting trees is overrated. We need an army of tree pruners.

Earlier this week I left my house, walked down the street and started snipping branches off of trees growing between the sidewalk and the roadway. When I encountered a limb too stout for my loppers, I grabbed a hand saw. Within a couple of hours, there were piles of branches up and down the block.

On its surface, the activity feels mundane. What could be more prosaic than pruning a few trees? But lately, I’ve begun to ask the opposite question: What could be more profound?

There’s a temptation to think that all we need to do for trees is stick them in the ground. But that couldn’t be farther from the case: To live full lives, especially in cities where we ask them to grow in conditions far removed from the forests where they’ve evolved, trees need our continued attention and care. And of all the things we can do for trees, I’ve come to believe that pruning is one of the most durable actions we can take — and one of the most powerful ways we can speak to the future.

So I’m here to convince you that tree planting as a solitary act has been oversold and overhyped. Pruning, my friends, is where it’s at.

Let me explain…

Tree planting is overrated

As you likely know if you haven’t been living in a cave, tree planting has become the environmental solution du jour, promoted to address every problem from urban heat islands to air pollution to biodiversity loss to global climate change. Even noted non-environmentalist Donald Trump endorsed it. (Will we ever be able to unsee the dreadfully awkward scene of Trump and Emmanuel Macron shoveling dirt onto a sapling on the White House lawn while their wives looked on?)

Trump is gone (for now at least), and so is the tree he and Macron co-planted, but tree planting as a virtuous, all-encompassing solution remains. There’s a well-funded global trillion tree campaign. The U.S. government and The Nature Conservancy each want to plant a billion trees. Here in Maryland alone we’re supposed to get 5 million new trees.

I’ve seen the excitement that can be mustered for tree plantings. Volunteers arrive eager with their shovels, and nothing is easier than getting a politician (see again Trump, above) or corporate leader to scoop some dirt onto a tree for a photo opp. Then the volunteers and politicians disappear, and the tree begins what could be — but, too often, is not — a very long life.

To be clear, tree planting is wonderful and important work. I’ve been involved in the planting of hundreds of trees, mostly in the town where I live outside Washington, DC. I’m sure I will plant many more trees.

But tree planting is also overrated, because it’s so often framed as a one-time, commitment-free action that singlehandedly addresses a problem. It’s not. If a tree is planted but not cared for, especially in a city, it will probably grow poorly, live a truncated life and fail to provide much benefit for anyone. In fact, it may do more harm than good, saddling cities with maintenance costs they can’t afford and potentially turning residents off of trees for decades to come.

Don’t just plant. Prune!

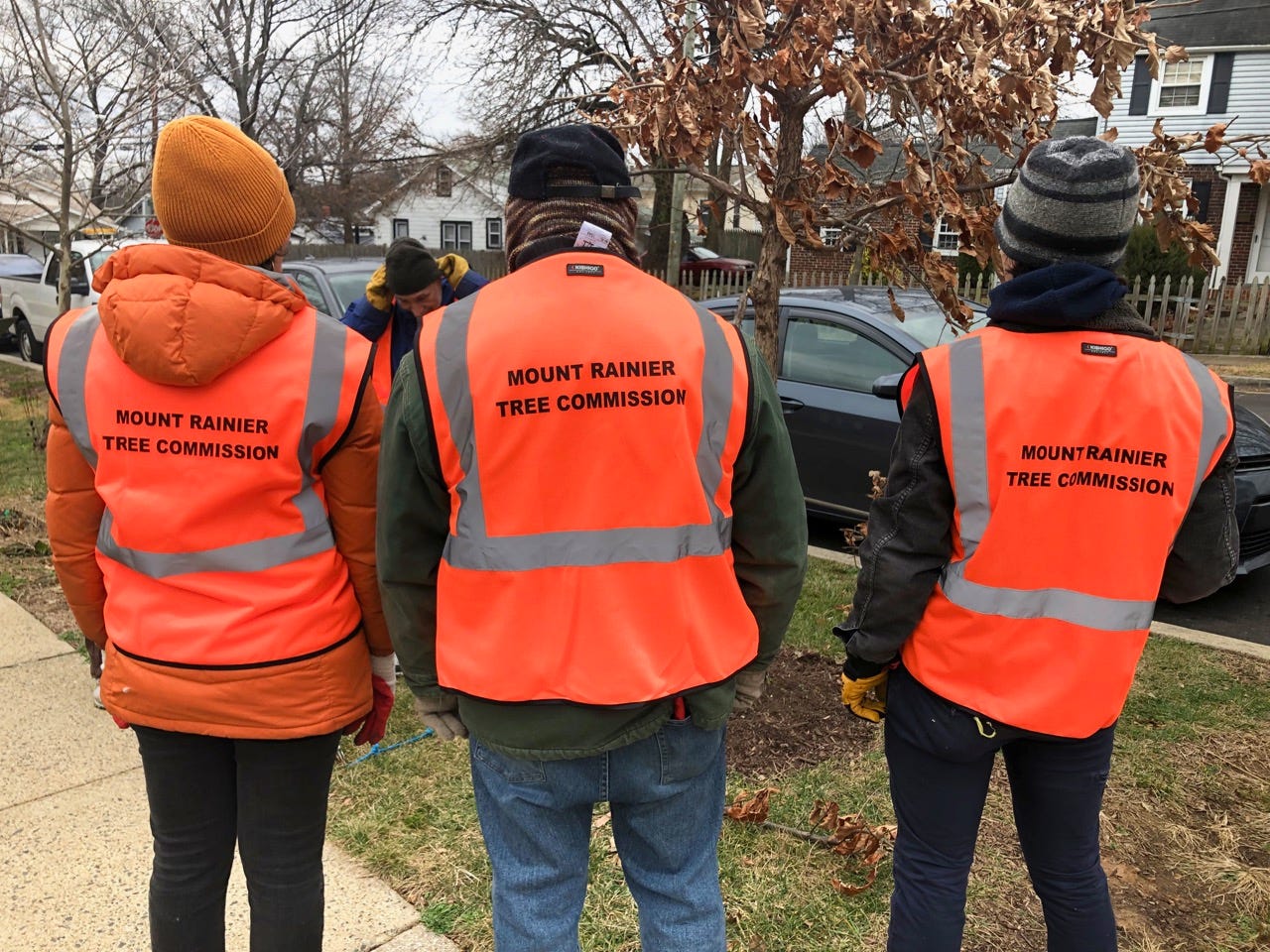

So instead of planting trees this winter, I’m pruning them. And, perhaps not surprisingly, I feel especially drawn toward the trees near my house. I, along with other volunteers on my neighborhood’s tree commission, planted many of these trees in 2018. For one especially tree-deprived block, we chose a mix of more than a dozen species: basswood, baldcypress, tulip poplar, red maple, red oak, swamp white oak, redbud, hackberry, sycamore, willow oak, bur oak, river birch, fringe tree.

I don’t know anywhere else you could find such diversity on a single city block. Far more common would be a row of even-aged red maples or willow oaks. This might offer a pleasing regularity reminiscent of a formal garden like Versailles, but it can come with a steep cost. If a disease, insect or other stressor hits, it could kill all the trees at once, leaving that block denuded. And even if that doesn’t happen, a uniform stand of trees will likely reach the end of life around the same time, leading to a costly wave of tree removals and canopy loss. Plus, a whole block of the same tree is just plain BORING. Leave Versailles in Versailles — we can do better!

Five years in, our trees are starting to look like real trees, though still somewhat awkward and gangly. In human terms, they’re a bit like middle-schoolers: growing into their mature selves, but not yet ready for full independence. We still have work to do.

I’ve learned over the years that planting a tree is easy, and growing a tree to its full potential is much harder. And because it’s hard, it’s also way more exciting.

That’s because every tree offers an intellectual puzzle combined with a physical challenge. My job is to figure out what the tree needs and then carry it out. One might need lower limbs removed, so it can direct its resources toward growing upward. Another might need help “deciding” which of two competing upward-pointing branches should be the “leader” — in other words, one branch should be snipped off or shortened so the other can take the lead. A third tree might need some interior branches snipped off so they don’t create a weak structure or rub against each other, which can open wounds where disease can get in. A fourth may need all of the above.1

I realize this may all seem like helicopter tree parenting. Trees grow in the forest just fine without human help, we’re often told. (The reality is more complicated, but that’s for another post.) Can’t they grow just as well in cities?

It’s important to remember that the trees we’re growing cities are wild species. With few exceptions, they were not designed or bred to grow in urban environments. (And most of those exceptions, such as the Bradford pear, have fallen out of favor.)

We’ve plucked our urban trees from the forest and asked them to do things they did not evolve to do: live for decades in tiny spaces surrounded by pavement and provide us city dwellers with shade, beauty, cooling, health benefits, happiness. It’s amazing that wild forest trees grow at all in the puny boxes of compacted soil we offer them, much less that many seem to thrive there. It’s easy to imagine a world in which trees thrust into such environments simply shriveled and died.

In the forest, a tree’s life is shaped by its neighbors, who force it to grow skyward with one main stem reaching for the light. Trees in forests self-prune as they grow, shedding lower branches when they no longer capture enough sunlight to be worth the metabolic cost of maintenance.

Trees in cities, freed from competition, often “forget” to self prune or form a leader. Instead, spread grow branches outward, often horizontally. They’re seeking light, and when you have no one above you, going out gets you more than going up. But that’s not what we want. We want our trees to become strong, stately, shade-casting giants that will endure for decades — and to avoid conflicts with pedestrians and delivery trucks that tend to end poorly for trees. So we need to assume the role of arboreal forest neighbors and shape our trees.

It’s a daunting task. Some of the trees I’m pruning are already several times my height, and they’re just getting started. Some could — should — outlive me. With luck, they will improve the lives of people who aren’t even born yet — people I will never know. As the world warms, they will become ever more important. To have so much at stake is almost overwhelming. To think I can meaningfully shape the lives of such massive, long-lived beings can feel like the height of hubris.

But then I remind myself, if I don’t do it, who will? Our small city has almost no money to pay someone to care for trees, and my fellow volunteer pruners are busy in other parts of the city. So I put my doubts aside, pick up my tools and get to work.

Speaking to the future

I fear that only a small fraction of the millions, billions or trillion trees planted will get this kind of care. I’ve seen countless grants for tree planting. I can’t recall ever seeing a grant for tree pruning or long-term care, even though pruning can account for 40 percent of a city’s tree-related expenditures — up to eight times the cost of tree planting. (That’s mostly pruning of big trees with machines, not the early structural pruning I do from the ground, but structural pruning can reduce future maintenance costs.)

Thanks in large part to my neighbor and tree pruning mentor Barry Stahl, I think we in Mount Rainier, almost by accident, have stumbled upon a model of community-led tree care that works, if perhaps not perfectly, as well as any city program I’m aware of. It requires a special combination of factors: a skilled leader (Barry), a critical mass of motivated volunteers and a city government willing to trust its residents (possibly a reflection of limited resources). Tree commissioners and several others are authorized to prune public trees, including street trees.

Hundreds of people walk by our trees every day. Sometimes dogs poop on them and occasionally one is vandalized, which can be distressing. Few people probably give them — or their caretakers — much thought as they hurry about their lives. But we do. Barry put this beautifully and profoundly the other day, when he said, “We have a duty to these trees and to the community. But we also have a privilege. Nobody else gets to look at them and know them the way we do.”

Perhaps it’s an effect of reaching middle age, but I’ve been thinking a lot lately about what I’m supposed to be doing in this world. Our society has become so wealthy and our technology so powerful that many of us find ourselves more in search of meaning than in need of things that used to drive people, like food or money. The writing I produce for my day job can feel intangible, ephemeral. I know I wrote dozens of stories in 2018, the year we planted these trees. I would struggle to tell you from memory what any of them were about. Some were written for outlets that no longer exist. The longer they recede into the past, the less relevant any of them are.

These trees are real, physical beings. I can run my hands over their bark, smell their flowers, brush their leaves against my cheek. When I prune them, they respond; if I’m attuned to these responses, I can care for them better. It’s a positive feedback loop.

As my long-ago writings fade into obscurity, exerting less and less impact on the world with each passing year, these trees grow taller and more relevant.

I believe we are meant to interact, physically and meaningfully, with the world. We are not just brains in jars, as much as the online life can give that impression; we are bodies with senses, muscles, nerve endings. For many of us, our bodies are so underutilized that we need to invent reasons to exercise them. Pruning trees is meaningful bodily work. It awakens ancestral connections between human bodies, tools and wood: three things that have been in contact and communication for as long as our species has existed.

Soon, perhaps as soon as next year, some of the trees I’ve been pruning will grow beyond my reach. Like a parent sending their child off to college, I will have to let them go, trusting them to take care of themselves. I already feel wistful.

If you’re feeling inspired to pick up your loppers and saw, I’ve created a simple tree pruning guide that you can find here. There are many more detailed ones available online. Indeed, there are whole books about tree pruning. Please limit your pruning to trees on your own property or ones you have permission to prune.

This Chillum block (2398-2300 Drexel St, Hyattsville, MD 20783) has freshly planted trees all around but the trees are horridly shaped, with crisscrossed interior branches, no leads, gaping wounds, etc. They needed to be pruned years ago, before they were ever planted on the street. It's painful to see.